Dopamine, Casinos, and Social Media

April 24, 2020

By: Ben

Dopamine Drips

I use a bad Twitter client. I can only download tweets from the last hour, it shows them to me in order, shows me no tweets my followers "liked", and to see threads I have to open them in a separate browser on my phone. While these inconveniences would be horrible for some folks using Twitter, it also means I'm better able to break out of the addiction loop that Twitter sets up to keep you on social media.

Twitter promises to let you "See what’s happening in the world right now" and they deliver on the promise. It feels great to read information from smart folks, and I try to follow a variety of reporters, researchers, and academics who have expertise in areas I want to learn more about. The problem with using Twitter and other social networks is how they manipulate your feed in order to keep your attention for as long as possible.

When doing activities like scrolling through Twitter, our brains releases a magic chemical called dopamine. Dopamine gives us a feeling of elation, release, and general happiness. This dopamine feedback loop (here's a pop-psychology article on it) is what drives our addiction to a game, a social media feed, or a slot machine. The problem is, when we do a fun activity regularly, our brain releases dopamine in smaller quantities. Eventually any fun activity becomes boring.

A method that game designers use to counteract our boredom is to give us positive feedback to our games randomly. When we gain positive feedback randomly, our brain actually releases more dopamine for an activity that we're used to. Game designers also extend the time it takes to gain positive feedback to longer and longer durations, delaying the dopamine feedback in order for it to have a greater effect. While not an exhaustive list, just these two techniques are heavy influences in common game design tropes: higher levels needing more experience points, prevalence of loot boxes, the simple algorithm behind "clicker" games, and the list goes on. A designer is incentivized to keep the player's interest in their game for as long as possible, and many players seek out games that hold their interest for hours.

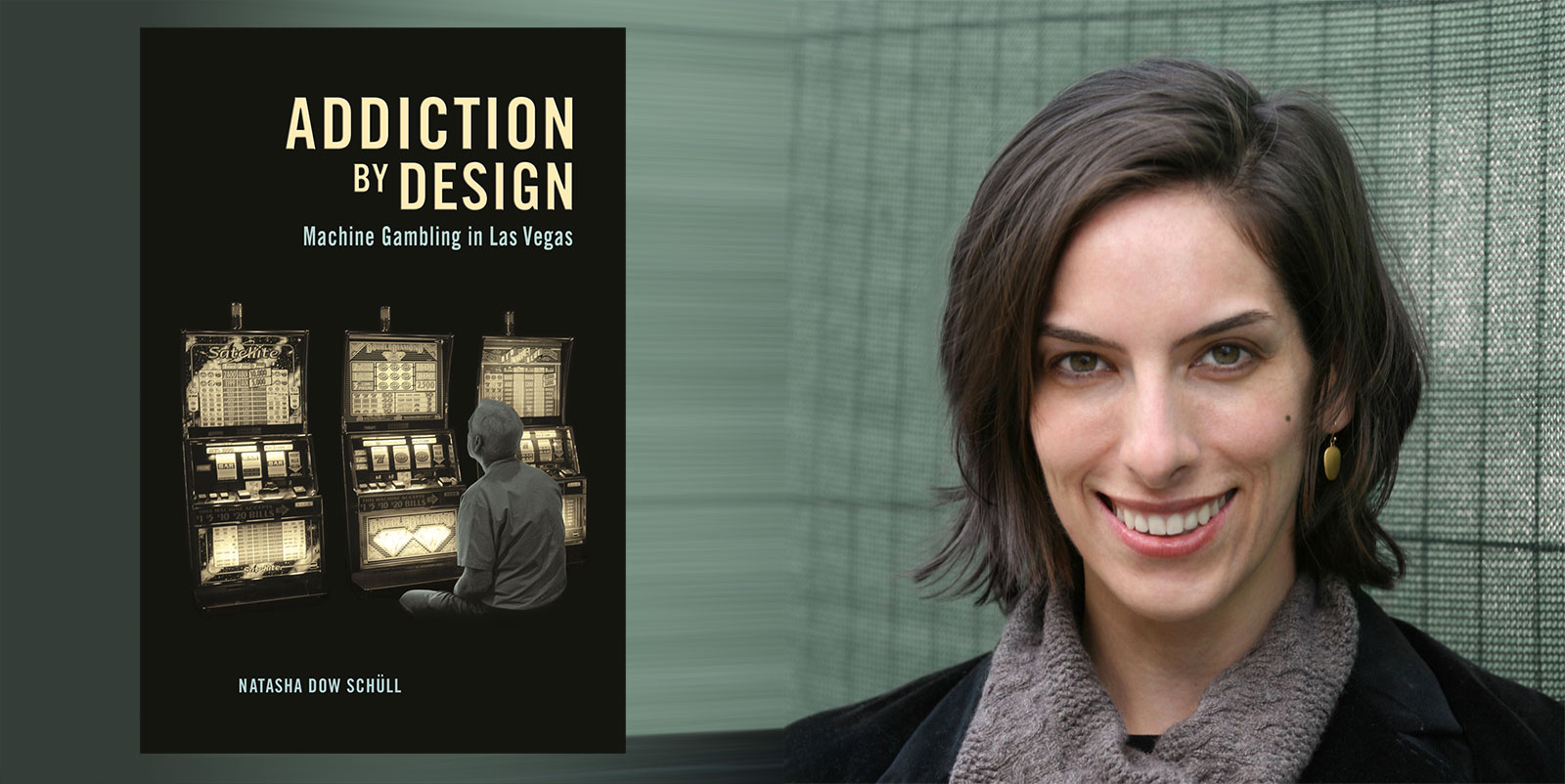

Addiction by Design

While the field of game design has honed the dopamine feedback loop into a myriad variations for every type of player, there's one subset of the gaming industry that has perfected it: the casino industry. Addiction by Design by Natasha Dow Schüll details the techniques that casinos use to keep players in the "zone," a state where they loose track of time, enjoy the audio visual experience of the video slot machine in front of them, and – most importantly for the casino industry – keep feeding money into the machine. If you're a designer, I recommend reading the book as it details the environmental design of casinos, button ergonomics, casino economics, and the design of the most addicting algorithms driving the video slot machine design.

Schull's work is grounded in casino and gambling-based game design, but even a quick scan of the text reveals the same design considerations in many other industries. This leads me back to the other industry besides games that derives massive profits from one's continual engagement: social media.

Social networks gain ad revenue for the length and engagement that a user spends on them. Their astronomical profits depend on people spending an increasing amount of time viewing advertising. Because people get bored with the same activity over and over, social media companies employ the similar techniques that casino designers use.

For example, social networks don't show your friends' or people you follows' posts in chronological order. Instead, they develop algorithms to feed users content at intervals delayed based on one's interaction history and interest profile. Similar to algorithms on a slot machine that produce small wins right when a player might lose interest, the stream of interactions given to the user produce positive feedback distributed meticulously to ensure continual scrolling.

Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn all show snippets of stories from external sources. These snippets give users a brief overview of what the story contains, but also disincentivizes users from leaving the platform. A snappy headline and a sentence or two from the article is all a user needs to interact with an article, and thus gain valuable psychometric information to show a user more targeted advertising. Casinos also disincentivize their patrons from leaving. Schull devotes an entire chapter outlining the environmental and interior design practices to entice gamblers in, and keep them feeding their slot machine.

I'm unsure the engineers at Instagram, Facebook, or LinkedIn intended to create feedback loops cloned from slot machines, but the company's underlying motivation is the same as at International Game Technology: to increase profits. The slot machine industry attracts and retains players with flashing lights, sound design, and the promise of quick riches. Social media attracts and retains users by manipulating our need for human contact and novel information. The pervasive use of an algorithmically generated, infinitely scrolling newsfeed serves the same purpose as the reels of a slot machine.

User Centered Design

There's another similarity between the design of casinos and social networks: user centered design. User or human centered design follows the basic principle that you work with people who use your product to design it. The designer then iterates on their design based on the user's or player's feedback in order to create something that the user/player and folks like them would love to have. The ultimate goal is to create a product meets the requirements of what a customer will buy and what a company is willing to produce. When what a customer will spend is attention and what the company produces are methods of captivation, addiction is the most profitable model.

My reasons for using Twitter is to gain useful information about a variety of topics, but the techniques that keep me on social media for long periods of time are not based on those motivations. People often start playing slots for the promise of winning money, but heavily addicted players profiled in Schull's book stop caring about the money and only want to keep playing. People start social media to keep up with their friends, but the reason we stay online much longer than it takes to see how many children our high school acquaintances produced is because the design of the platforms is set up to make sure we keep scrolling.

Design tools are there for us as designers to connect to the needs of the people we design for, and careful iteration in conversation with users can create better products for people to enjoy. Design tools like user or human centered design does not automatically remove the possibility of exploitation just because we're connecting directly with our users. Designers also have to ensure their designs aren't contributing to a system of addiction.

Because of my study of game design, I understand the addiction loops in media around me, but that doesn't mean I'm immune to them. That's why I use a "bad" Twitter client; it helps me regulate and question my interaction with a valuable, entertaining, but ultimately addicting information source. While the profit motives of social media are the root cause of creating addiction loops, without a broader societal change we're not going to see them change any time soon. In the meantime we need to find methods to regulate the addictive techniques motivating us to keep scrolling.